The Many Treasures in Natural History Collections

July 8, 2025

Two large gastropod (snail) shells from the Hazard collection in the new exhibit on mollusks in the Museum of the Earth: Triplofusus giganteus from the Florida Keys (left) and Charonia tritonis from the Solomon Islands (right).

In early 2025, the staff of the Paleontological Research Institution (PRI) were working on plans for a major new temporary exhibit on mollusks for our Museum of the Earth. We were not worried about having enough specimens of clams, snails, and cephalopods to display. PRI’s Research Collection is among the best in the country for mollusks both fossil and modern (more about this below). But we were a little concerned that we might not have enough shells for visitors to handle, especially groups of K-12 students coming for educational programs. We do not use specimens from the Research Collection for these purposes since they might be damaged, which would lessen their scientific value. We regularly put shells from newly donated collections that have little or no information about where they were found in our Education Collection (because that information is essential for doing research), but it had been a while since we had been given a lot of such specimens.

It was therefore timely that we received an inquiry from Dan Schult, a math professor at Colgate University in Hamilton, New York, about an hour and a half drive from Ithaca, who said he had been cleaning out his stepfather’s storage unit and found his collection of “seashells”. He said he was looking for a place that could use the shells for some good educational purpose. He described its size as about 8-9 medium boxes (“So it’s a lot”).

Even though we thought we needed the shells, we were nonetheless a little hesitant to say yes immediately. Because of major staff reductions at PRI that took place in late 2023, we had instituted a general moratorium on taking major new collection donations. We just didn’t have the staff available to process them. Professor Schult, however, said he did not think there was much in the way of accompanying information, which we thought would likely mean that processing would not take much time. So we agreed to take the collection.

The collection Dan Schult gave us was made over many decades by his stepfather, John Steven (“Steve”) Hazard (1931-2020), who was a prolific artist specializing in prints and etchings in a variety of styles, including still life. A gallery in Chicago that displayed his work said that his “etchings combine myth with the industrial age and often represent the sensory overload brought on from the multi-media of the modern world and the social chaos of ancient history.” Hazard, the gallery’s notice continued, had “the ability to draw and subsequently etch anything and everything well and in great detail. His painstaking technique leaves no detail overlooked and his imagination is magical.” Hazard’s works are in many collections across the country, including the Smithsonian.

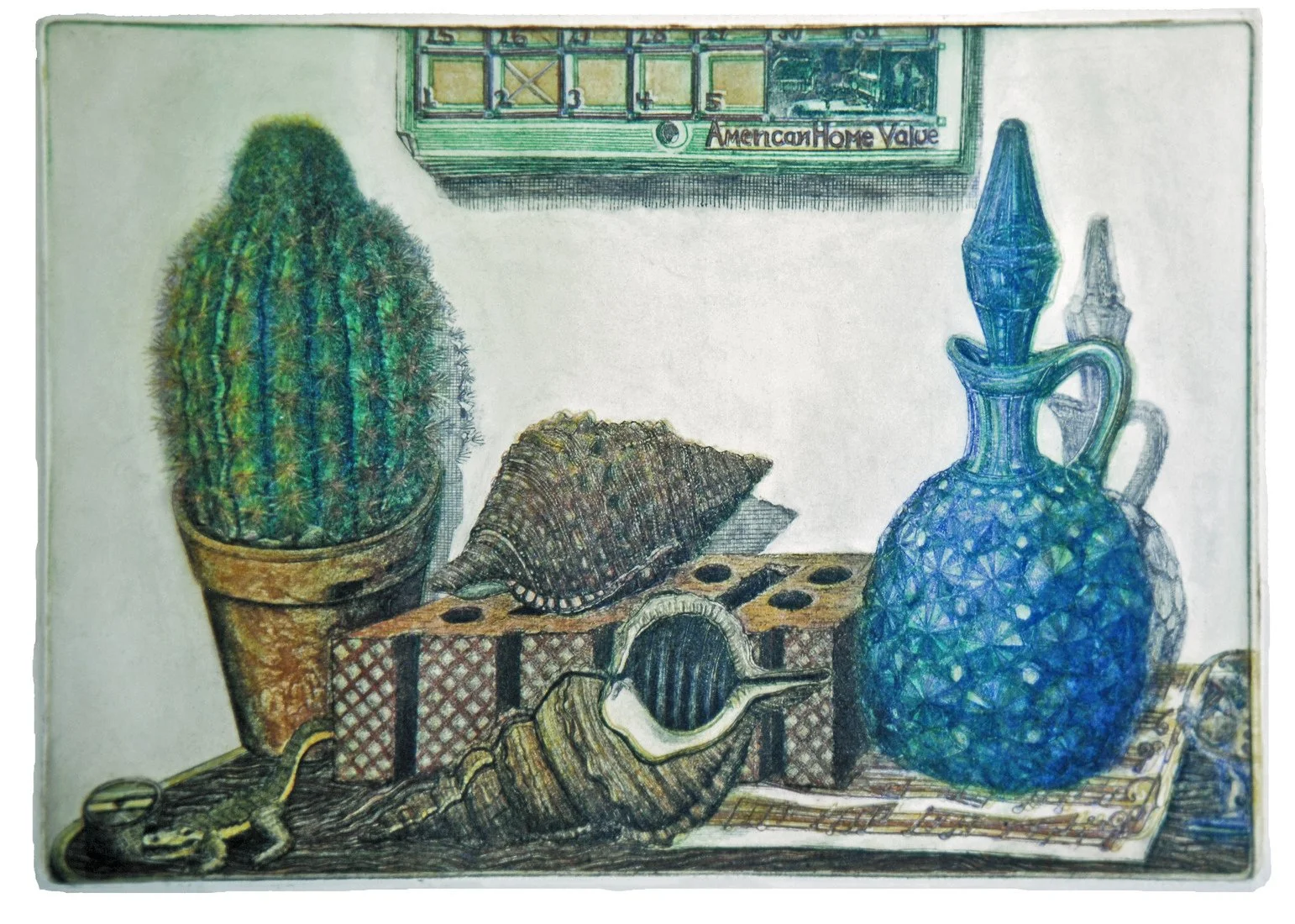

Hazard's interest in art began in his youth and evolved over time through his attendance at Michigan State University, where he earned his bachelor's degree in art history. He was particularly fascinated by the shape of marine gastropod (snail) shells and began to collect them, specializing in the families Cymatiidae (also known as tritons) and Bursidae (frog shells). Shells from his collection appeared in some of his artwork, such as this color etching titled "Mementos".

Mementos by Steven Hazard, 11-color etching. This piece of art features shells from Hazard’s personal collection.

The collection arrived in early April and we began to examine it. Indeed, many of the shells did not seem to have much in the way of information about where they were collected. But a lot of them did, and those specimens were quite spectacular. The shells had clearly been accumulated by someone who valued them. Although they had been stored in a wide variety of very unconventional containers, like glass jars that had once held instant coffee and baby food, almost all were in excellent condition. Since there was no one else available on staff to deal with the collection, I spent about a week opening every box and jar and sorting through what turned out to be about 2000 specimens. The results were enriching in a surprising variety of ways.

About half of the shells had labels rolled up and stuffed tightly into their apertures.

About half of the shells had small pieces of paper tucked into them. These makeshift labels were often torn shreds of yellow legal paper or newspaper, or sometimes formal printed labels from dealers from whom the shells had been purchased. Many were so tightly folded that they had to be unwound with tweezers and carefully flattened before they could be read. Some labels had notes, presumably written by Hazard, about the habitat where the shell was found (deep, shallow, “on coral rubble”, etc.), and even about their relative rarity in the area or unusual variations of shell form.

Steve Hazard was clearly well-traveled, with a lot of friends in a lot of places. The localities on these various labels spanned the Indian and Western Pacific oceans, as well as outliers like the Canary and Easter Islands. Many localities were familiar to me mainly from my reading about battles in the Pacific in World War II, such as Guadalcanal or Peleliu. The area with the largest number of labels was the Philippines, followed by Australia. Sri Lanka was well represented as was New Zealand and the Red Sea.

Alas, so many beautiful and unusual shells had no little bits of paper stuffed into them. This is a frequent disappointment in dealing with donated collections. One of the most important aspects of a specimen in a natural history museum research collection is information about where it came from. Indeed, the major difference between a collection made as a hobby or aesthetic pleasure and one kept for research is the data associated with it – mainly about where the specimens were collected. Specimens without such data are much less valuable for scientific research. This is because using a natural history specimen – like a modern mollusk shell – to learn something about its evolution or ecology almost always requires knowing where the organism originally lived. (For fossils, there is an additional question: how old is it? Geography helps here too, because knowing the location frequently can tell us what rock layer a fossil came from.) This means that keeping locality information together with specimens is one of the most important aspects of collection care. By the time they make it to a museum like ours, some specimens have lost all record of their original source in nature, and unfortunately, we cannot go back in time to retrieve information that was lost or never recorded.

In our museum, these specimens with “no data” almost never are added to the research collection. They are first inspected by staff in our Education Department to see if they are useful for teaching, which can mean serving anyone from pre-K to college students to the general public. If so, they are added to our Education Collection, which is completely separate from our Research Collection. If Education can’t use them, they go onto shelves labeled “Teacher Resource Day”, which is our very popular annual event at which we give away thousands of surplus specimens to educators from across Central New York. (We have done this for more than 30 years, and it remains one of my favorite events, because teachers who come are so eager to learn and grateful to add to their often meager classroom resources.)

Many of the shells had been stored in old glass jars.

Specimens with adequate data are then added to the Research Collection. The first and crucial step in this process is “accessioning”, which is museum jargon for formally accepting an object into our care. Accessioning means associating a number with a specimen or specimens that come from a particular source (donor, expedition) at a particular time (whether one or several thousand). Once assigned, the accession number will remain with the specimen(s) permanently, even if additional numbers are given later. Once a specimen is accessioned, it falls under our collections policies which govern how we will treat and maintain the object in perpetuity. According to these policies (which are very similar to those in almost all modern collection-based museums) we cannot get rid of a specimen unless and until it is de-accessioned, a process that requires a paperwork trail and formal approval of the Science Committee of our Board of Trustees. The reason for all this formality is at the heart of the mission of a collection-based museum: our policies demonstrate that we care for and make available objects in our collection not as “ours” but on behalf of the public, as a public good. The policies are the guarantee that we will take care of valuable objects which people have entrusted to our custody. They ensure that people who make specimen donations can have confidence that we will use the specimens in a way that maximizes their benefit to society.

Once a specimen gets an accession number, it may go in a box on a shelf with some kind of label that allows it to be located later. Or it may move along what is sometimes called a “curatorial continuum”, the steps of which vary depending on the case or who may want to use it. They may include identification (what species is it); physical preparation, cleaning, conservation, or repair; detailed examination and imaging; and then assignment of a unique catalog number. The PRI collection contains more than 7 million accessioned specimens, but fewer than 200,000 are cataloged. Then there is entering catalog information into a digital database, which usually includes the specimens’ locality information. The latter is called “georeferencing” and may be especially time-intensive (because, for example, locality names have changed or need to be translated, and then latitude and longitude determined).

Doing all this takes a lot of time and a lot of money. Different kinds of specimens take different amounts of effort, but it is not uncommon in our museum for accessioning, labeling, boxing, and storing a single specimen to take 15 minutes. Cataloging and georeferencing may take an hour. Photography adds even more time. Multiply the time for these steps by the number of specimens in a large collection and it can be a daunting task. This is one reason that natural history museums have to be selective about what specimens they accept and accession (the other obvious reason being physical space).

But the result of all this work is a collection of specimens that is fully and easily accessible for research and exhibit, a public good similar to a library of books or a gallery of paintings or sculpture. These are all sources of potential knowledge and inspiration, of potential solutions to future problems or questions that we may not be able to imagine right now. Imaging and digitization can help preserve aspects of such collections, but they can never fully duplicate all of their qualities, which is why they are maintained permanently. Scientists and students from around the world use our collection every year to answer questions about past and present biodiversity, evolution, climate change, geological history, and conservation. We provide almost all of these services at no charge, as a public service.

One of the two shells with the rolls of $20 bills.

One of the greatest pleasures and values of a well-curated natural history collection is that you never know in advance what you will discover. When looking for one thing you are frequently surprised to find another. Opening our drawers and boxes is like traveling around the world and through time, finding new things. Despite our enormous knowledge of the natural world, we are still profoundly ignorant of so much of it. For marine mollusks, like those in the Hazard collection, scientists are discovering new species every year. For most of the tens of thousands of the species already named, we know little about their distribution and ecology. Many species are uncommon or are from areas rarely visited by scientific study, and so it’s difficult to learn about the variability of these species, or the changes they undergo during their lifetimes. These qualities are discoverable in collections because sufficient specimens have accumulated through the efforts of many collectors over decades or even centuries. Museum specimens are also signposts to where more information can potentially be found, at localities that have yet to be adequately explored, and, sadly, at localities that no longer exist in their original state due to human activity. Collections are the only places we can go to study extinct species, whether they lived a million years ago or only a decade. They are the only records we have of the history and distribution of life on our planet. In most cases, they can never be duplicated or replaced.

The Hazard collection contained another unexpected find which is unique in my almost 50 year career in museums. In two of the largest triton shells (Charonia tritonis) from the Western Pacific, two large rolls of $20 bills were stuffed. We reported this pleasant discovery to Dan Schult, who generously allowed us to keep it as a donation. Would that all collections that came to us came with such assistance!

The end result of Steve Hazard’s passion and industry and Dan Schult’s generosity was the addition of more than 1000 specimens to PRI’s Research Collection of modern mollusks, mainly from the gastropod families Cancellariidae and Bursidae from the Indo-Pacific region, in which it turns out our collection was rather sparse. An equal number of beautiful shells are going into our Education Collection, which will allow us to do much more than we had planned in the way of hands-on activities in the Museum connected to our new exhibit, which also includes several of the Hazard specimens. You just never know. Which is why collections like ours will always be sources of treasure.