PRI's Wonderful Life

By Dr. Warren Allmon, Director of the Paleontological Research Institution

December 30, 2025

The holidays are a time for “Christmas movies” in my house, and one that is always on our list is Frank Capra’s 1947 “It’s a Wonderful Life” (we’re not alone; Google AI calls it “the gold standard for Christmas movies”). In the film, a man named George Bailey gets to see what the world would have been like had he never been born. (The holiday connection is mostly because the last part takes place around Christmas.) This movie has more than just seasonal significance for me and for many other paleontologists because of a best-selling and much-discussed 1989 book by my former professor Stephen J. Gould. In Wonderful Life (1989), Gould wonders what the history of life would be like if we could “run the tape again”, his point being that it is unlikely that the same evolutionary results would be produced.

I have also long connected the film to the history of my own institution. Like so much of life, the Paleontological Research Institution (PRI) was a product of historical contingency, an unlikely event that almost didn’t happen. PRI’s founder, Cornell professor Gilbert Harris, started his little organization literally in his back yard in 1932, with little money but a lot of determination. It survived and grew because of the quality of the work that its tiny staff carried out, and the generosity of a few loyal friends. Because of this unusual origin story, late Cornell President Emeritus Frank Rhodes once affectionately described PRI as “quirky and improbable”.

But when I sat down with my family for our annual viewing over the recent holidays, it wasn’t just my former professor’s book or PRI’s founding that came to mind. For I realized that not only was PRI itself unlikely, it had also recently had a George Bailey experience of another kind.

In the movie, George sticks by his family’s struggling Building and Loan business, foregoing college and a higher salary, because it serves the community, and along the way he helps a lot of people. But when financial catastrophe strikes, he thinks his life is not worth living, until his guardian angel shows him a world in which he had never existed. Having realized that he has indeed made a positive difference in the lives of so many people, George runs home to his family, and at the end of the film a huge crowd rushes into the living room and covers the table with more than enough money to bail him out.

George Bailey and his family in, “It’s A Wonderful Life” (1946) Public Domain Image

Financial catastrophe also recently struck PRI. In 2023, it became clear that our largest donor would be unable to fulfill pledges of more than $30 million, and PRI laid off half of its staff and faced foreclosure because we could not pay our $3 million mortgage. The donor’s pledges were not just for the mortgage. They covered the entire range of the Institution’s operations, including general operating support and salaries. Although in retrospect it seems like we should have known that depending so much on a single donor was risky, this donor had given us more than $20 million over the past 20 years, and had always come through before. We depended on them and did not have a fallback plan.

After more or less suffering in silence for a year, because we hoped that the donor would recover and make good on their promises or that Cornell might help us, we at last appealed to the wider world through the media. On January 13, 2025, an article appeared in The Ithaca Voice, and the following day a Cornell alum who had known our second Director, Katherine Palmer, in the 1960s gave us $1 million. Suddenly our situation was transformed. Additional gifts came in, and sales of our plush toy line soared. We made a deal with the holder of our mortgage debt to pay interest only (13%) for a year and we started to imagine that we could survive. We received a second $1 million gift in May, as we also opened a major new temporary exhibit (funded by grants), demonstrating that we were still very much alive and serving our community.

Another major setback occurred at around this time, when we were told that we would have to evacuate a building that the same donor had promised to donate to us. So we spent much of the second half of 2025 not just serving our audiences and raising money, but also packing hundreds of boxes of library books and specimen collections for a move to a rented warehouse. This also further increased the pressure on our finances.

By late summer, although gifts continued to arrive at roughly twice the rate of previous “normal” years, larger gifts had slowed and we were still about $1 million away from being able to pay off our mortgage. But in early October one of our Board members wrote a short letter to The Ithaca Times, and this resulted in a front page story. At around the same time, we hired a public relations firm to assist us in getting the word out to other media. Eventually, these efforts began to show results. We were featured in an article in the Albany Times Union, and several radio and TV news spots across the state. Donations began to increase.

It wasn’t just adults who offered to help. Alex Howard, age 14, lives in Horseheads, NY, near Elmira. He has wanted to be a paleontologist for as long as he can remember. He and his mother Liz have been volunteers in the Museum of the Earth for the past year, since the family moved from Philadelphia. After he heard about PRI’s financial trouble, Alex wanted to do something about it. He put together a display board with information about PRI and showed it at an event put on by the Finger Lakes Gem, Mineral & Fossil Club in Corning on November 22. He solicited donations for PRI from attendees, and gave fossils from his own collection to each donor. His efforts raised more than $2,400. I passed Alex’s story on to our PR firm, and as a result he and his mom were interviewed on CBS Morning News in early December and also mentioned in a story about PRI’s situation that appeared in The New York Times on December 18.

Alex Howard and his family at the Finger Lakes Gem, Mineral & Fossil Club in Corning, NY

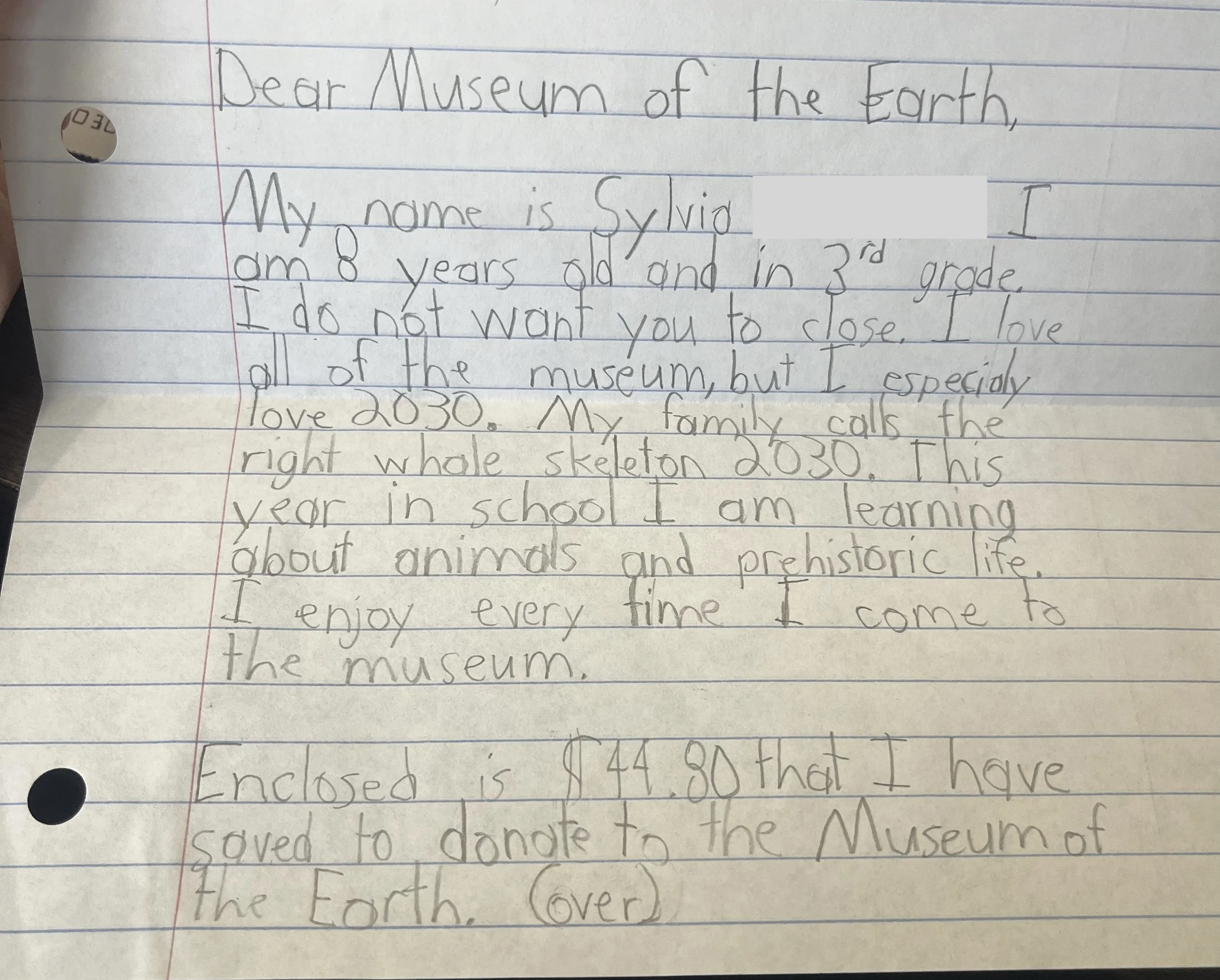

On November 7, we received a hand-written note from an 8-year-old girl who said she did not want us to close. She enclosed $40.80 “that I have saved to donate to the Museum of the Earth.” On December 11, we received a note from the family in Syracuse. “Our 8-year-old daughter said that all she wanted for Christmas was to support the Museum”, they wrote, and enclosed a check for $1000.

Letter from a young Museum of the Earth fan

Professionals also stepped up to do their part. One in particular, Professor Carlton Brett of the University of Cincinnati, made it a mission to raise awareness and funds, tirelessly contacting colleagues and friends of friends. The two largest professional organizations of paleontologists in the country, the Paleontological Society and SEPM/Society of Sedimentary Geology, took the very unusual step of including a fundraising appeal in their regular communications to their members. More donations came in.

As a result of all of this activity, plus a few unexpected windfalls of government funding and bequests, altogether PRI raised $4,469,603 in calendar 2025, enough to pay off our entire mortgage and remain solvent through the June 30, 2026, the end of our fiscal year.

If we are not quite, as George Bailey is called at the end of “Wonderful Life”, the “richest man in town”, PRI has apparently been saved for much the same reason that he was: over our almost 100 year history, we have mattered to a lot of people, from a lot of different places and backgrounds, and those people gave generously in our hour of need. We have mattered to local families and children who come to the Museum of the Earth. We have mattered to Cornell students who have been mentored by our staff, and Cornell faculty who see the value we bring to the University. We have mattered to professional and amateur paleontologists across the country, who value the vast collection of specimens that we care for and make available and the scientific journal we have published since 1895. We have mattered to K-12 teachers, who have brought their classes to PRI and benefited from our educator professional development. We have mattered to the more than 1 million people who access our online educational content every year. Our extraordinary year of giving came from all of these groups of people, reflecting PRI’s role as a full-service, albeit small, natural history museum for Ithaca, upstate New York, and the nation. Just as George Bailey changed the lives of his neighbors in Bedford Falls, PRI has changed lives in our many communities, near and far. When teachers and students have needed us, we have been here, regardless of their ability to pay. When science itself has been threatened by assaults on teaching evolution and climate change, we have responded with innovative and award-winning programming. When valuable and historic specimen collections have been orphaned, we have adopted them so that they can remain available for research and education.

All of these accomplishments have been possible because, like George Bailey, PRI’s staff have worked tirelessly and sacrificed greatly for many years. It is astonishing and humbling to me to witness their dedication to our mission and our audiences. They have done the impossible with the inadequate for an unimaginable length of time. Our Board of Trustees (all volunteers) have also worked incredibly long hours, given generously of their money and advice and expertise, and have supported the staff every way they could.

Our collective achievement is enormous, and means that the immediate threat of foreclosure and shutdown, and the scattering of our collection to other institutions, is not imminent. But we are not out of the woods. In the months and years ahead, PRI must find solutions to many pressing issues, including caring for our specimen collection, paying our staff, and maintaining our facilities. We will need new partners, and we will need to raise a lot of money. These are real challenges, but the experience of the past year demonstrates that there are people out there willing to help.

What would the world have been like had PRI never existed? Without a guardian angel to do the experiment, we will never know. But we do know that what PRI does now is important to a lot of people, and that knowledge fuels our determination to continue to do what we do for the benefit of as many people as we can for as long as we can. Just like George Bailey.